Posts tagged sterling

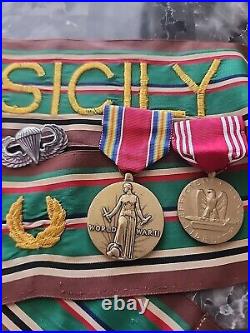

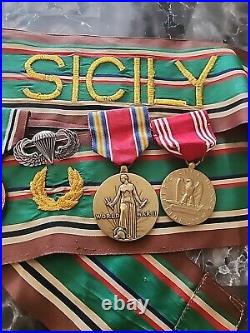

PLEASE FOLLOW OUR E BAY STORE. PLEASE READ WHOLE ADD. We do not want your feed back. We want your repeat business. We get by having best prices on the net. NOTE :STERLING JUMP WINGS. Banner is apx 30 inch’s. The Allied invasion of Sicily, also known as the Battle of Sicily and Operation Husky, was a major campaign of World War II in which the Allied forces invaded the island of Sicily in July 1943 and took it from the Axis powers (Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany). It began with a large amphibious and airborne operation, followed by a six-week land campaign, and initiated the Italian campaign. To divert some of the Axis forces to other areas, the Allies engaged in several deception operations, the most famous and successful of which was Operation Mincemeat. Husky began on the night of 9-10 July 1943 and ended on 17 August. These events led to the fall of the Fascist regime in Italy with Italian dictator Benito Mussolini being ousted, and to the Allied invasion of Italy on 3 September. The German leader, Adolf Hitler, “canceled a major offensive at Kursk after only a week, in part to divert forces to Italy, ” resulting in a reduction of German strength on the Eastern Front. [16] The collapse of Italy necessitated German troops replacing the Italians in Italy and to a lesser extent the Balkans, resulting in one-fifth of the entire German army being diverted from the east to southern Europe, a proportion that would remain until near the end of the war. Main article: Operation Husky order of battle. The plan for Operation Husky called for the amphibious assault of Sicily by two Allied armies, one landing on the south-eastern and one on the central southern coast. The amphibious assaults were to be supported by naval gunfire, as well as tactical bombing, interdiction and close air support by the combined air forces. As such, the operation required a complex command structure, incorporating land, naval and air forces. The overall commander was American General Dwight D. Eisenhower, as Commander-in-Chief (C-in-C) of all the Allied forces in North Africa. British General Sir Harold Alexander acted as his second-in-command and as the 15th Army Group commander. The American Major General Walter Bedell Smith was appointed as Eisenhower’s Chief of Staff. [18] The overall Naval Force Commander was the British Admiral Sir Andrew Cunningham. The Allied land forces were from the American, British and Canadian armies, and were structured as two task forces. The Eastern Task Force (also known as Task Force 545) was led by General Sir Bernard Montgomery and consisted of the British Eighth Army (which included the 1st Canadian Infantry Division). The Western Task Force (Task Force 343) was commanded by Lieutenant General George S. Patton and consisted of the American Seventh Army. The two task force commanders reported to Alexander as commander of the 15th Army Group. Seventh Army consisted initially of three infantry divisions, organized under II Corps, commanded by Lieutenant General Omar Bradley. The 1st and 3rd Infantry Divisions, commanded by Major Generals Terry Allen and Lucian Truscott respectively, sailed from ports in Tunisia, while the 45th Infantry Division, under Major General Troy H. Middleton, sailed from the United States via Oran in Algeria. The 2nd Armored Division, under Major General Hugh Joseph Gaffey, also sailing from Oran, was to be a floating reserve and be fed into combat as required. On 15 July, Patton reorganized his command into two corps by creating a new Provisional Corps headquarters, commanded by his deputy army commander, Major General Geoffrey Keyes. The British Eighth Army had four infantry divisions and an independent infantry brigade organized under XIII Corps, commanded by Lieutenant-General Sir Miles Dempsey, and XXX Corps, commanded by Lieutenant-General Sir Oliver Leese. The two divisions of XIII Corps, the 5th and 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Divisions, commanded by Major-Generals Horatio Berney-Ficklin and Sidney Kirkman, sailed from Suez in Egypt. The formations of XXX Corps sailed from more diverse ports: the 1st Canadian Infantry Division, under Major-General Guy Simonds, sailed from the United Kingdom, the 51st (Highland) Infantry Division, under Major-General Douglas Wimberley, from Tunisia and Malta, and the 231st Independent Infantry Brigade Group from Suez. The 1st Canadian Infantry Division was included in Operation Husky at the insistence of the Canadian Prime Minister, William Mackenzie King, and the Canadian Military Headquarters in the United Kingdom. This request was granted by the British, displacing the veteran British 3rd Infantry Division. The change was not finalized until 27 April 1943, when Lieutenant-General Andrew McNaughton, then commanding the Canadian First Army in the United Kingdom, deemed Operation Husky to be a viable military undertaking and agreed to the detachment of both the 1st Canadian Infantry Division and the 1st Canadian Tank Brigade. The “Red Patch Division” was added to Leese’s XXX Corps to become part of the British Eighth Army. In addition to the amphibious landings, airborne troops were to be flown in to support both the Western and Eastern Task Forces. To the east, the British 1st Airborne Division, commanded by Major-General George F. Hopkinson, was to seize vital bridges and high ground in support of the British Eighth Army. The initial plan dictated that the U. 82nd Airborne Division, commanded by Major General Matthew Ridgway, was to be held as a tactical reserve in Tunisia. Allied naval forces were also grouped into two task forces to transport and support the invading armies. The Eastern Naval Task Force was formed from the British Mediterranean Fleet and was commanded by Admiral Bertram Ramsay. The Western Naval Task Force was formed around the U. Eighth Fleet, commanded by Admiral Henry Kent Hewitt. The two naval task force commanders reported to Admiral Cunningham as overall Naval Forces Commander. [19] Two sloops of the Royal Indian Navy – HMIS Sutlej and HMIS Jumna – also participated. At the time of Operation Husky, the Allied air forces in North Africa and the Mediterranean were organized into the Mediterranean Air Command (MAC) under Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Tedder. The major sub-command of MAC was the Northwest African Air Forces (NAAF) under the command of Lieutenant General Carl Spaatz with headquarters in Tunisia. NAAF consisted primarily of groups from the United States 12th Air Force, 9th Air Force, and the British Royal Air Force (RAF) that provided the primary air support for the operation. Other groups from the 9th Air Force under Lieutenant General Lewis H. Brereton operating from Tunisia and Egypt, and Air H. Malta under Air Vice-Marshal Sir Keith Park operating from the island of Malta, also provided important air support. Army Air Force 9th Air Force’s medium bombers and P-40 fighters that were detached to NAAF’s Northwest African Tactical Air Force under the command of Air Marshal Sir Arthur Coningham moved to southern airfields on Sicily as soon they were secured. At the time, the 9th Air Force was a sub-command of RAF Middle East Command under Air Chief Marshal Sir Sholto Douglas. Middle East Command, like NAAF and Air H. Malta were sub-commands of MAC under Tedder who reported to Eisenhower for NAAF operations[19] and to the British Chiefs of Staff for Air H. Malta and Middle East Command operations. The island was defended by the two corps of the Italian 6th Army under General Alfredo Guzzoni, although specially designated Fortress Areas around the main ports (Piazze Militari Marittime), were commanded by admirals subordinate to Naval Headquarters and independent of the 6th Army. [26] In early July, the total Axis force in Sicily was about 200,000 Italian troops, 32,000 German troops and 30,000 Luftwaffe ground staff. The main German formations were the Panzer Division Hermann Göring and the 15th Panzergrenadier Division. The Panzer division had 99 tanks in two battalions but was short of infantry (with only three battalions), while the 15th Panzergrenadier Division had three grenadier regiments and a tank battalion with 60 tanks. [27] About half of the Italian troops were formed into four front-line infantry divisions and headquarters troops; the remainder were support troops or inferior coastal divisions and coastal brigades. Guzzoni’s defence plan was for the coastal formations to form a screen to receive the invasion and allow time for the field divisions further back to intervene. By late July, the German units had been reinforced, principally by elements of the 1st Parachute Division, 29th Panzergrenadier Division and the XIV Panzer Corps headquarters (General der Panzertruppe Hans-Valentin Hube), bringing the number of German troops to around 70,000. [29] Until the arrival of the corps headquarters, the two German divisions were nominally under Italian tactical control. The panzer division, with a reinforced infantry regiment from the panzergrenadier division to compensate for its lack of infantry, was under Italian XVI Corps and the rest of the panzergrenadier division under the Italian XII Corps. [30] The German commanders in Sicily were contemptuous of their allies and German units took their orders from the German liaison officer attached to the 6th Army HQ, Generalleutnant Fridolin von Senger und Etterlin who was subordinate to Generalfeldmarschall Albert Kesselring, the German C-in-C Army Command South (OB Süd). Von Senger had arrived in Sicily in late June as part of a German plan to gain greater operational control of its units. [31] Guzzoni agreed from 16 July to delegate to Hube control of all sectors where there were German units involved, and from 2 August, he commanded the Sicilian front. Two American and two British attacks by airborne troops were carried out just after midnight on the night of 9-10 July, as part of the invasion. The American paratroopers consisted largely of Colonel James M. Gavin’s 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment (expanded into the 505th Parachute Regimental Combat Team with the addition of the 3rd Battalion of the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment, along with the 456th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion, Company’B’ of the 307th Airborne Engineer Battalion and other supporting units) of the U. 82nd Airborne Division, making their first combat drop. The British landings were preceded by pathfinders of the 21st Independent Parachute Company, who were to mark landing zones for the troops who were intending to seize the Ponte Grande, the bridge over the River Anape just south of Syracuse, and hold it until the British 5th Infantry Division arrived from the beaches at Cassibile, some eleven kilometres (7 mi) to the south. [55] Glider infantry from the British 1st Airborne Division’s 1st Airlanding Brigade, commanded by Brigadier Philip Hicks, were to seize landing zones inland. Strong winds of up to 70 km/h (45 mph)[57] blew the troop-carrying aircraft off course and the American force was scattered widely over south-east Sicily between Gela and Syracuse. By 14 July, about two-thirds of the 505th had managed to concentrate, and half the U. Paratroopers failed to reach their rallying points. [58] The British air-landing troops fared little better, with only 12 of the 147 gliders landing on target and 69 crashing into the sea, with over 200 men drowning. [59] Among those who landed in the sea were Major General George F. The scattered airborne troops attacked patrols and created confusion wherever possible. A platoon of the 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment, under Lieutenant Louis Withers, part of the British 1st Airlanding Brigade, landed on target, captured Ponte Grande and repulsed counterattacks. Additional paratroops rallied to the sound of shooting and by 08:30 89 men were holding the bridge. [60] By 11:30, a battalion of the Italian 75th Infantry Regiment (Colonel Francesco Ronco) from the 54th Infantry Division “Napoli” arrived with some artillery. [61] The British force held out until about 15:30 hours, when, low on ammunition and by now reduced to 18 men, they were forced to surrender, 45 minutes before the leading elements of the British 5th Division arrived from the south. [61][62] Despite these mishaps, the widespread landing of airborne troops, both American and British, had a positive effect as small isolated units, acting on their initiative, attacked vital points and created confusion.

PLEASE FOLLOW OUR E BAY STORE. PLEASE READ WHOLE ADD. We do not want your feed back. We want your repeat business. We get by having best prices on the net. Sub badge has sub hull number on it, very RARE!! Banner is apx 30 inch’s. First patrol, October 1943 – January 1944. Cod arrived in Brisbane, Australia, on 2 October 1943 to prepare for her first war patrol. She sailed from there 20 days later. Penetrating the South China Sea, she contacted few targets, and launched an attack only once, on 29 November, with unobserved results. Second patrol, February 1944 – March 1944. Cod put to sea for her second war patrol in the South China Sea, off Java, and off Halmahera. On 16 February, she surfaced to sink a sampan by gunfire, and on 23 February, torpedoed a Japanese merchantman. Third patrol, March 1944 – June 1944. Refitting at Fremantle again from 13 March – 6 April 1944, Cod sailed to the Sulu Sea and the South China Sea off Luzon for her third war patrol. Fourth patrol, July 1944 – August 1944. Cod was put to sea again 3 July on her fourth war patrol. She ranged from the coast of Luzon to Java. Fifth patrol, September 1944 – November 1944. Cod put to sea on her fifth war patrol 18 September 1944, bound for Philippine waters. Two days later, she inflicted heavy damage on a tanker. Contacting a large convoy on 25 October, Cod launched several attacks without success. With all her torpedoes expended, she continued to shadow the convoy for another day to report its position. In November she took up a lifeguard station off Luzon, ready to rescue carrier pilots carrying out the series of air strikes on Japanese bases which paved the way for the Battle of Leyte later that month. Sixth patrol, March 1945 – May 1945. On 24 March she sailed from Pearl Harbor for the East China Sea on her sixth war patrol. Assigned primarily to lifeguard duty, she used her deck gun to sink a tugboat and its tow on 17 April, rescuing three survivors, and on 24 April launched an attack on a convoy which resulted in the most severe depth charging of her career. The next day, she sent the minesweeper W-41 to the bottom. Foley and S1c Andrew G. Johnson were washed overboard while freeing the torpedo room hatch. S1c Foley was recovered the next morning, but QM2c Johnson drowned during the night. This was Cod’s only fatality during World War II. Seventh patrol, May 1945 – June 1946. O-19 stuck on Ladd Reef. After refitting at Guam between 29 May and 26 June 1945, Cod put out for the Gulf of Siam and the coast of Indo-China on her seventh war patrol. On 9 and 10 July she went to the rescue of a grounded Dutch submarine, O-19, taking its crew on board and destroying the Dutch submarine when it could not be gotten off the reef. This was the only international submarine-to-submarine rescue in history. After returning the Dutch sailors to U. Naval Base Subic Bay, between 21 July and 1 August Cod made 20 gunfire attacks on the junks, motor sampans, and barges which were all that remained to supply the Japanese at Singapore. After inspecting each contact to rescue civilian crew, Cod sank it by gunfire and torpedoes, sending to the bottom a total of 23. On 1 August, an enemy plane strafed Cod, forcing her to dive, leaving one of her boarding parties behind. The men were rescued two days later by USS Blenny (SS-324). During that celebration, the two crews learned of the Japanese surrender. To symbolize that moment, another symbol was added to Cod’s battle flag: the name O-19 under a martini glass. Cod sailed for home on 31 August. Arriving at Naval Submarine Base New London, on 3 November after a visit to Miami, Florida, Cod sailed to the Philadelphia Navy Yard for a overhaul, returning to New London, Connecticut where she was decommissioned and placed in reserve 22 June 1946. AGSS-224, 1 December 1962, IXSS-224, 30 June 1971. For her successful World War II. Since 1 May 1976. 1,525 long tons (1,549 t) surfaced. 2,424 long tons (2,463 t) submerged. 27 ft 3 in (8.31 m). 17 ft (5.2 m) maximum. 4 × General Motors. 2 × 126- cell. 4 × high-speed General Electric. 2,740 shp (2.0 MW) submerged. 11,000 nautical miles (13,000 mi) surfaced at 10 kn (12 mph). 48 hours at 2 kn (2.3 mph) submerged. 75 days on patrol. 6 officers, 54 enlisted. 10 × 21 inch (533 mm). (6 bow, 4 stern). 1 × 4/50 caliber gun. Later 1 x 5/25 caliber gun. And 20 mm Oerlikon. The Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal[1] was a United States military award of the Second World War, which was awarded to any member of the United States Armed Forces who served in the Asiatic-Pacific Theater from 1941 to 1945. The medal was created on November 6, 1942, by Executive Order 9265[2] issued by President Franklin D. The medal was designed by Thomas Hudson Jones; the reverse side was designed by Adolph Alexander Weinman which is the same design as used on the reverse of the American Campaign Medal and European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal. There were 21 Army and 48 Navy-Marine Corps official campaigns of the Pacific Theater, denoted on the suspension and service ribbon of the medal by service stars which also were called “battle stars”; some Navy construction battalion units issued the medal with Arabic numerals. The Arrowhead device is authorized for those campaigns which involved participation in amphibious assault landings. The Fleet Marine Force Combat Operation Insignia is also authorized for wear on the medal for Navy service members who participated in combat while assigned to a Marine Corps unit. The flag colors of the United States and Japan are visible in the ribbon. The Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal was first issued as a service ribbon in 1942. A full medal was authorized in 1947, the first of which was presented to General of the Army Douglas MacArthur. The European Theater equivalent of the medal was known as the European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal. Boundaries of Asiatic-Pacific Theater. (1) The eastern boundary is coincident with the western boundary of the American Theater. (2) The western boundary is from the North Pole south along the 60th meridian east longitude to its intersection with the east boundary of Iran, then south along the Iran boundary to the Gulf of Oman and the intersection of the 60th meridian east longitude, then south along the 60th meridian east longitude to the South Pole. US Navy – Marine Corps campaigns. The 43 officially recognized US Navy campaigns in the Pacific Theater of Operations are:[5]. Pearl Harbor: Pearl Harbor-Midway: 7 December 1941. Wake Island: 8-23 December 1941. Philippine Islands operation: 8 December 1941 – 6 May 1942. Netherlands East Indies engagements: 23 January – 27 February 1942. Pacific raids (1942): 1 February – 10 March 1942. Coral Sea: 4-8 May 1942. Midway: 3-6 June 1942. Guadalcanal-Tulagi landings: 7-9 August 1942 (First Savo). Capture and defense of Guadalcanal: 10 August 1942 – 8 February 1943. Makin Raid: 17-18 August 1942. Eastern Solomons: 23-25 August 1942. Buin-Faisi-Tonolai raid: 5 October 1942. Cape Esperance: 11-12 October 1942 (Second Savo). Santa Cruz Islands: 26 October 1942. Guadalcanal: 12-15 November 1942 (Third Savo). Tassafaronga: 30 November – 1 December 1942 (Fourth Savo). Eastern New Guinea operation: 17 December 1942 – 24 July 1944. Rennel Island: 29-30 January 1943. Consolidation of Solomon Islands: 8 February 1943 – 15 March 1945. Aleutians operation: 26 March – 2 June 1943. New Georgia Group operation: 20 June – 16 October 1943. Bismarck Archipelago operation: 25 June 1943 – 1 May 1944. Pacific raids (1943): 31 August – 6 October 1943. Treasury-Bougainville operation: 27 October – 15 December 1943. Gilbert Islands operation: 13 November – 8 December 1943. Marshall Islands operation: 26 November 1943 – 2 March 1944. Asiatic-Pacific raids (1944): 16 February – 9 October 1944. Western New Guinea operations: 21 April 1944 – 9 January 1945. Marianas operation: 10 June – 27 August 1944. Western Caroline Islands operation: 31 August – 14 October 1944. Leyte operation: 10 October – 29 November 1944. Luzon operation: 12 December 1944 – 1 April 1945. Iwo Jima operation 15 February – 16 March 1945. Okinawa Gunto operation: 17 March – 30 June 1945. Third Fleet operations against Japan: 10 July – 15 August 1945. Kurile Islands operation: 1 February 1944 – 11 August 1945. Borneo operations: 27 April – 20 July 1945. Tinian capture and occupation: 24 July – 1 August 1944. Consolidation of the Southern Philippines: 28 February – 20 July 1945. Hollandia operation: 21 April – 1 June 1944. Manila Bay-Bicol operations: 29 January – 16 April 1945. Escort, antisubmarine, armed guard and special operations: 7 December 1941 – 2 September 1945. Submarine War Patrols (Pacific): 7 December 1941 – 2 September 1945.

This vintage WW2 sterling silver 2-piece “Son in Service” medal, measuring 0.5 inches by 0.5 inches, is a poignant piece of military history. The medal was commonly worn by families to signify that their son was serving in the armed forces during World War II. The two-piece design is a classic feature of these medals, and this piece is in good coverall condition with general wear consistent with its age. A significant and personal collectible for WWII memorabilia enthusiasts. Condition : Good coverall condition; general wear; kindly see photos. Measurements : 0.5 inches (height), 0.5 inches (width). Please reach out with any questions or offers. We are always around to chat. Check out all Brooklyn Artifacts items here!

PLEASE FOLLOW OUR E BAY STORE. PLEASE READ WHOLE ADD. We do not want your feed back. We want your repeat business. We get by having best prices on the net. NOTE :SUB BADGE IS POST WW2- PRE 1960. Banner is apx 30 inch’s. Submarine action in Palawan Passage (23 October 1944). Note: This action is referred to by Morison as’The Fight in Palawan Passage’. And elsewhere, occasionally, as the’Battle of Palawan Passage’. As it sortied from its base in Brunei. Kurita’s powerful “Center Force” consisted of five battleships Yamato. Ten heavy cruisers Atago. , two light cruisers Noshiro. Around midnight on 22-23 October. The American submarines Darter. Were positioned together on the surface close by. At 01:16 on 23 October, Darter. S radar detected the Japanese formation in the Palawan Passage. At a range of 30,000 yd (27,000 m). Her captain promptly made visual contact. At least one of these was picked up by a radio operator on Yamato, but Kurita failed to take appropriate antisubmarine precautions. Darter and Dace traveled on the surface at full power for several hours and gained a position ahead of Kurita’s formation, with the intention of making a submerged attack at first light. This attack was unusually successful. At 05:24, Darter fired a salvo of six torpedoes, at least four of which hit Kurita’s flagship. The heavy cruiser Atago. Ten minutes later, Darter made two hits on Atago. Takao, with another spread of torpedoes. At 05:56, Dace made four torpedo hits on the heavy cruiser Maya (sister to Atago and Takao). Atago and Maya quickly sank. Atago sank so rapidly that Kurita was forced to swim to survive. He was rescued by the Japanese destroyer Kishinami. And then later transferred to the battleship Yamato. Takao turned back to Brunei, escorted by two destroyers, and was followed by the two submarines. On 24 October, as the submarines continued to shadow the damaged cruiser, Darter ran aground on the Bombay Shoal. All efforts to get her off failed; she was abandoned; and her entire crew was rescued by Dace. Efforts to scuttle Darter over the course of the next week all failed, including torpedoes from Dace and Rock. That hit the reef (and not Darter) and deck-gun shelling from Dace and later Nautilus. After multiple hits from his 6-inch deck guns. The Nautilus commander determined on 31 October that the equipment on Darter was only good for scrap and left her there. The Japanese did not bother with the wreck. Takao retired to Singapore. Being joined in January 1945 by Myoko, as the Japanese deemed both crippled cruisers irreparable and left them moored in the harbor as floating anti-aircraft batteries. The Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal. Was a United States. Of the Second World War. Which was awarded to any member of the United States Armed Forces. Who served in the Asiatic-Pacific Theater. From 1941 to 1945. The medal was created on November 6, 1942, by Executive Order. Issued by President Franklin D. The medal was designed by Thomas Hudson Jones. The reverse side was designed by Adolph Alexander Weinman. Which is the same design as used on the reverse of the American Campaign Medal. And European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal. There were 21 Army and 48 Navy-Marine Corps official campaigns of the Pacific Theater, denoted on the suspension and service ribbon. Of the medal by service stars. Which also were called “battle stars”; some Navy construction battalion. Units issued the medal with Arabic numerals. Is authorized for those campaigns which involved participation in amphibious assault landings. The Fleet Marine Force Combat Operation Insignia. Is also authorized for wear on the medal for Navy service members who participated in combat while assigned to a Marine Corps unit. The flag colors of the United States and Japan. Are visible in the ribbon. The Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal was first issued as a service ribbon in 1942. A full medal was authorized in 1947, the first of which was presented to General of the Army. Equivalent of the medal was known as the European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal. Boundaries of Asiatic-Pacific Theater. (1) The eastern boundary is coincident with the western boundary of the American Theater. (2) The western boundary is from the North Pole south along the 60th meridian east longitude to its intersection with the east boundary of Iran, then south along the Iran boundary to the Gulf of Oman and the intersection of the 60th meridian east longitude, then south along the 60th meridian east longitude to the South Pole. US Navy – Marine Corps campaigns. The 43 officially recognized US Navy campaigns in the Pacific Theater of Operations are. Pearl Harbor: Pearl Harbor. 8 December 1941 – 6 May 1942. Netherlands East Indies engagements. 23 January – 27 February 1942. 1 February – 10 March 1942. 7-9 August 1942 (First Savo). Capture and defense of Guadalcanal. 10 August 1942 – 8 February 1943. Buin-Faisi-Tonolai raid: 5 October 1942. 11-12 October 1942 (Second Savo). 12-15 November 1942 (Third Savo). 30 November – 1 December 1942 (Fourth Savo). Eastern New Guinea operation. 17 December 1942 – 24 July 1944. Consolidation of Solomon Islands. 8 February 1943 – 15 March 1945. 26 March – 2 June 1943. New Georgia Group operation. 20 June – 16 October 1943. Bismarck Archipelago operation: 25 June 1943 – 1 May 1944. Pacific raids (1943): 31 August – 6 October 1943. Operation: 27 October – 15 December 1943. 13 November – 8 December 1943. 26 November 1943 – 2 March 1944. Asiatic-Pacific raids (1944): 16 February – 9 October 1944. Western New Guinea operations. 21 April 1944 – 9 January 1945. 10 June – 27 August 1944. Western Caroline Islands operation. 31 August – 14 October 1944. 10 October – 29 November 1944. 12 December 1944 – 1 April 1945. 15 February – 16 March 1945. 17 March – 30 June 1945. Third Fleet operations against Japan. 10 July – 15 August 1945. 1 February 1944 – 11 August 1945. 27 April – 20 July 1945. Tinian capture and occupation. 24 July – 1 August 1944. Consolidation of the Southern Philippines. 28 February – 20 July 1945. 21 April – 1 June 1944. 29 January – 16 April 1945. Escort, antisubmarine, armed guard and special operations: 7 December 1941 – 2 September 1945. Submarine War Patrols (Pacific). 7 December 1941 – 2 September 1945.

PLEASE FOLLOW OUR E BAY STORE. SALE SEE OUR STORE. PLEASE READ WHOLE ADD. We do not want your feed back. We want your repeat business. We get that by posting new items at a fair price. World War I Victory Medal (United States). World War I Victory Medal. Service between April 6, 1917, and November 11, 1918, or with either of the following expeditions. American Expeditionary Forces in European Russia. Between November 12, 1918, and August 5, 1919. American Expeditionary Forces Siberia. Between November 23, 1918, and April 1, 1920. 36 millimeters in diameter. Is a winged Victory. Standing full length and full face. On the reverse is the inscription The Great War for Civilization and the coat of arms for the United States. Surmounted by a fasces. And on either side the names of the Allied and Associated Nations. The medal is suspended by a ring. 1 3/8 inches in length and 36 millimeters in width, composed of two rainbows. And having the red in the middle, with a white thread along each edge. And Secretary of the Navy. The Great War for Civilization. Mexican Border Service Medal. Army of Occupation of Germany Medal. The World War I Victory Medal known prior to establishment of the World War II Victory Medal. In 1945 simply as the Victory Medal was a United States. Designed by James Earle Fraser. Of New York City. Under the direction of the Commission of Fine Arts. Award of a common allied. Service medal was recommended by an inter-allied committee in March 1919. Each allied nation would design a’Victory Medal’ for award to their military personnel, all issues having certain common features, including a winged figure of victory. On the obverse and the same ribbon. The Victory Medal was originally intended to be established by an act of Congress. Authorizing the medal never passed, however, thus leaving the military departments to establish it through general orders. Published orders in April 1919, and the Navy. In June of the same year. The Victory Medal was awarded to military personnel for service between April 6, 1917, and November 11, 1918, or with either of the following expeditions. The front of the bronze medal features a winged Victory. Holding a shield and sword on the front. The back of the bronze medal features “The Great War For Civilization” in all capital letters curved along the top of the medal. Curved along the bottom of the back of the medal are six stars, three on either side of the center column of seven staffs wrapped in a cord. The top of the staff has a round ball on top and is winged on the side. The staff is on top of a shield that says “U” on the left side of the staff and “S” on the right side of the staff. On left side of the staff it lists one World War I Allied. Country per line: France. On the right side of the staff the Allied country names read: Great Britain. (spelled with a U instead of an O as it is spelled now), and China. Back of the medal. To denote battle participation and campaign credit, the World War I Victory Medal was authorized with a large variety of devices to denote specific accomplishments. In order of seniority, the devices authorized to the World War I Victory Medal were as follows. To the World War I Victory Medal was authorized by the United States Congress on February 4, 1919. Inch silver star was authorized to be worn on the ribbon of the Victory Medal for any member of the U. Army who had been cited for gallantry in action between 1917 and 1920. In 1932, the Citation Star (“Silver Star”) was redesigned and renamed the Silver Star Medal. And, upon application to the United States War Department. Any holder of the Silver Star Citation could have it converted to a Silver Star medal. The Navy Commendation Star. To the World War I Victory Medal was authorized to any person who had been commended by the Secretary of the Navy for performance of duty during the First World War. Inch silver star was worn on the World War I Victory Medal, identical in appearance to the Army’s Citation Star. Unlike the Army’s version, however, the Navy Commendation Star could not be upgraded to the Silver Star medal.

PLEASE FOLLOW OUR E BAY STORE. SALE SEE OUR STORE. PLEASE READ WHOLE ADD. We do not want your feed back. We want your repeat business. We get that by posting new items at a fair price. Service involving flying over the Atlantic Ocean. World War I Victory Medal (United States). World War I Victory Medal. Service between April 6, 1917, and November 11, 1918, or with either of the following expeditions. American Expeditionary Forces in European Russia. Between November 12, 1918, and August 5, 1919. American Expeditionary Forces Siberia. Between November 23, 1918, and April 1, 1920. 36 millimeters in diameter. Is a winged Victory. Standing full length and full face. On the reverse is the inscription The Great War for Civilization and the coat of arms for the United States. Surmounted by a fasces. And on either side the names of the Allied and Associated Nations. The medal is suspended by a ring. 1 3/8 inches in length and 36 millimeters in width, composed of two rainbows. And having the red in the middle, with a white thread along each edge. And Secretary of the Navy. The Great War for Civilization. Mexican Border Service Medal. Army of Occupation of Germany Medal. The World War I Victory Medal known prior to establishment of the World War II Victory Medal. In 1945 simply as the Victory Medal was a United States. Designed by James Earle Fraser. Of New York City. Under the direction of the Commission of Fine Arts. Award of a common allied. Service medal was recommended by an inter-allied committee in March 1919. Each allied nation would design a’Victory Medal’ for award to their military personnel, all issues having certain common features, including a winged figure of victory. On the obverse and the same ribbon. The Victory Medal was originally intended to be established by an act of Congress. Authorizing the medal never passed, however, thus leaving the military departments to establish it through general orders. Published orders in April 1919, and the Navy. In June of the same year. The Victory Medal was awarded to military personnel for service between April 6, 1917, and November 11, 1918, or with either of the following expeditions. The front of the bronze medal features a winged Victory. Holding a shield and sword on the front. The back of the bronze medal features “The Great War For Civilization” in all capital letters curved along the top of the medal. Curved along the bottom of the back of the medal are six stars, three on either side of the center column of seven staffs wrapped in a cord. The top of the staff has a round ball on top and is winged on the side. The staff is on top of a shield that says “U” on the left side of the staff and “S” on the right side of the staff. On left side of the staff it lists one World War I Allied. Country per line: France. On the right side of the staff the Allied country names read: Great Britain. (spelled with a U instead of an O as it is spelled now), and China. Back of the medal. To denote battle participation and campaign credit, the World War I Victory Medal was authorized with a large variety of devices to denote specific accomplishments. In order of seniority, the devices authorized to the World War I Victory Medal were as follows. To the World War I Victory Medal was authorized by the United States Congress on February 4, 1919. Inch silver star was authorized to be worn on the ribbon of the Victory Medal for any member of the U. Army who had been cited for gallantry in action between 1917 and 1920. In 1932, the Citation Star (“Silver Star”) was redesigned and renamed the Silver Star Medal. And, upon application to the United States War Department. Any holder of the Silver Star Citation could have it converted to a Silver Star medal. The Navy Commendation Star. To the World War I Victory Medal was authorized to any person who had been commended by the Secretary of the Navy for performance of duty during the First World War. Inch silver star was worn on the World War I Victory Medal, identical in appearance to the Army’s Citation Star. Unlike the Army’s version, however, the Navy Commendation Star could not be upgraded to the Silver Star medal.

PLEASE FOLLOW OUR E BAY STORE. SALE SEE OUR STORE. PLEASE READ WHOLE ADD. We do not want your feed back. We want your repeat business. We get that by posting new items at a fair price. SUB BADGE MADE BY MYERS. Main article: Allied submarines in the Pacific War. Japanese freighter Nittsu Maru sinks after being torpedoed by USS Wahoo. On 21 March 1943. Doctrine in the inter-war years emphasized the submarine as a scout for the battle fleet, and also extreme caution in command. Both these axioms were proven wrong after the attack on Pearl Harbor. The submarine skippers of the fleet boats of World War II. Waged a very effective campaign. Against Japanese merchant vessels, eventually repeating and surpassing Germany’s initial success during the Battle of the Atlantic. Against the United Kingdom. Size of Japanese merchant fleet during World War II (all figures in tons). End of period total. During the war, submarines of the United States Navy. Were responsible for 55% of Japan’s merchant marine. Losses; other Allied navies added to the toll. The Navy adopted an official policy of unrestricted submarine warfare. And it appears the policy was executed without the knowledge or prior consent of the government. The London Naval Treaty. To which the U. Required submarines to abide by prize rules. (commonly known as “cruiser rules”). It did not prohibit arming merchantmen. But arming them, or having them report contact with submarines or raiders. , made them de facto naval auxiliaries and removed the protection of the cruiser rules. This made restrictions on submarines effectively moot. Navy submarines also conducted reconnaissance patrols, landed special forces. Troops and performed search and rescue. Only 1.6 percent of the total U. Naval manpower was responsible for America’s success on its Pacific high seas; more than half of the total tonnage sunk was credited to U. The tremendous accomplishments of American submarines were achieved at the expense of 52 subs with 374 officers and 3,131 enlisted volunteers lost during combat against Japan; Japan lost 128 submarines during the Second World War in Pacific waters. American casualty counts represent 16 percent of the U. Operational submarine officer corps and 13 percent of its enlisted force. Rescuing a pilot from USS Bunker Hill. In addition to their commerce raiding role, submarines also proved valuable in air-sea rescue. While in command of United States Navy. 50.1 Rear Admiral. Commander of Pacific Fleet Submarine Force. That submarines be stationed near targeted islands during aerial attacks. In what became known as the “Lifeboat League”, pilots were informed that they could ditch. Their damaged planes near these submarines or bail out. Nearby and be rescued by them. Initially, the rescue submarines met several obstacles, most important of which was the lack of communication between the submarines and aircraft in the area; this led to several Lifeguard League submarines being bombed or strafed. Possibly including the sinking of USS Seawolf (SS-197). And USS Dorado (SS-248). Airmen rescued by submarines during World War II. Days on Lifeguard station. As fighting in the Pacific theater. Intensified and broadened in geographic scope, the eventual creation of Standing Operating Procedure. (SOP TWO) led to several improvements such as the assignment of nearby submarines before air attacks, and the institution of reference points to allow pilots to report their location in the clear. After the capture of the Marianas. Targets such as Tokyo, about 1,500 mi (2,400 km) north of the Marianas. Were brought within range of B-29 attacks and Lifeguard League submarines began rescue operations along their flight paths. Submarine lifeguards spent a combined 3,272 days on rescue duty and rescued 502 men. Famous examples include the rescue of 22 airmen by the USS Tang. And the rescue of future U. By the USS Finback (SS-230).

This vintage sterling silver medal is a rare find for collectors and enthusiasts alike. Soldier design, this medal is a testament to the bravery and faith of those who served during World War II. The medal is in excellent shape and has been well-maintained, making it a great addition to any collection. The medal is perfect for those interested in collectibles, religion, and spirituality. It is a unique piece that showcases the intersection of Christianity and military history. This medal is a must-have for any serious collector or history buff. Measures 1 1/4 x 1 1/8 in.