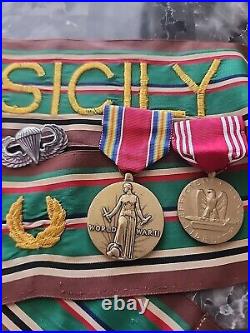

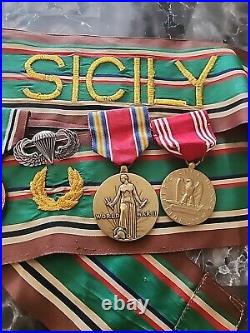

PLEASE FOLLOW OUR E BAY STORE. PLEASE READ WHOLE ADD. We do not want your feed back. We want your repeat business. We get by having best prices on the net. NOTE :STERLING JUMP WINGS. Banner is apx 30 inch’s. The Allied invasion of Sicily, also known as the Battle of Sicily and Operation Husky, was a major campaign of World War II in which the Allied forces invaded the island of Sicily in July 1943 and took it from the Axis powers (Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany). It began with a large amphibious and airborne operation, followed by a six-week land campaign, and initiated the Italian campaign. To divert some of the Axis forces to other areas, the Allies engaged in several deception operations, the most famous and successful of which was Operation Mincemeat. Husky began on the night of 9-10 July 1943 and ended on 17 August. These events led to the fall of the Fascist regime in Italy with Italian dictator Benito Mussolini being ousted, and to the Allied invasion of Italy on 3 September. The German leader, Adolf Hitler, “canceled a major offensive at Kursk after only a week, in part to divert forces to Italy, ” resulting in a reduction of German strength on the Eastern Front. [16] The collapse of Italy necessitated German troops replacing the Italians in Italy and to a lesser extent the Balkans, resulting in one-fifth of the entire German army being diverted from the east to southern Europe, a proportion that would remain until near the end of the war. Main article: Operation Husky order of battle. The plan for Operation Husky called for the amphibious assault of Sicily by two Allied armies, one landing on the south-eastern and one on the central southern coast. The amphibious assaults were to be supported by naval gunfire, as well as tactical bombing, interdiction and close air support by the combined air forces. As such, the operation required a complex command structure, incorporating land, naval and air forces. The overall commander was American General Dwight D. Eisenhower, as Commander-in-Chief (C-in-C) of all the Allied forces in North Africa. British General Sir Harold Alexander acted as his second-in-command and as the 15th Army Group commander. The American Major General Walter Bedell Smith was appointed as Eisenhower’s Chief of Staff. [18] The overall Naval Force Commander was the British Admiral Sir Andrew Cunningham. The Allied land forces were from the American, British and Canadian armies, and were structured as two task forces. The Eastern Task Force (also known as Task Force 545) was led by General Sir Bernard Montgomery and consisted of the British Eighth Army (which included the 1st Canadian Infantry Division). The Western Task Force (Task Force 343) was commanded by Lieutenant General George S. Patton and consisted of the American Seventh Army. The two task force commanders reported to Alexander as commander of the 15th Army Group. Seventh Army consisted initially of three infantry divisions, organized under II Corps, commanded by Lieutenant General Omar Bradley. The 1st and 3rd Infantry Divisions, commanded by Major Generals Terry Allen and Lucian Truscott respectively, sailed from ports in Tunisia, while the 45th Infantry Division, under Major General Troy H. Middleton, sailed from the United States via Oran in Algeria. The 2nd Armored Division, under Major General Hugh Joseph Gaffey, also sailing from Oran, was to be a floating reserve and be fed into combat as required. On 15 July, Patton reorganized his command into two corps by creating a new Provisional Corps headquarters, commanded by his deputy army commander, Major General Geoffrey Keyes. The British Eighth Army had four infantry divisions and an independent infantry brigade organized under XIII Corps, commanded by Lieutenant-General Sir Miles Dempsey, and XXX Corps, commanded by Lieutenant-General Sir Oliver Leese. The two divisions of XIII Corps, the 5th and 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Divisions, commanded by Major-Generals Horatio Berney-Ficklin and Sidney Kirkman, sailed from Suez in Egypt. The formations of XXX Corps sailed from more diverse ports: the 1st Canadian Infantry Division, under Major-General Guy Simonds, sailed from the United Kingdom, the 51st (Highland) Infantry Division, under Major-General Douglas Wimberley, from Tunisia and Malta, and the 231st Independent Infantry Brigade Group from Suez. The 1st Canadian Infantry Division was included in Operation Husky at the insistence of the Canadian Prime Minister, William Mackenzie King, and the Canadian Military Headquarters in the United Kingdom. This request was granted by the British, displacing the veteran British 3rd Infantry Division. The change was not finalized until 27 April 1943, when Lieutenant-General Andrew McNaughton, then commanding the Canadian First Army in the United Kingdom, deemed Operation Husky to be a viable military undertaking and agreed to the detachment of both the 1st Canadian Infantry Division and the 1st Canadian Tank Brigade. The “Red Patch Division” was added to Leese’s XXX Corps to become part of the British Eighth Army. In addition to the amphibious landings, airborne troops were to be flown in to support both the Western and Eastern Task Forces. To the east, the British 1st Airborne Division, commanded by Major-General George F. Hopkinson, was to seize vital bridges and high ground in support of the British Eighth Army. The initial plan dictated that the U. 82nd Airborne Division, commanded by Major General Matthew Ridgway, was to be held as a tactical reserve in Tunisia. Allied naval forces were also grouped into two task forces to transport and support the invading armies. The Eastern Naval Task Force was formed from the British Mediterranean Fleet and was commanded by Admiral Bertram Ramsay. The Western Naval Task Force was formed around the U. Eighth Fleet, commanded by Admiral Henry Kent Hewitt. The two naval task force commanders reported to Admiral Cunningham as overall Naval Forces Commander. [19] Two sloops of the Royal Indian Navy – HMIS Sutlej and HMIS Jumna – also participated. At the time of Operation Husky, the Allied air forces in North Africa and the Mediterranean were organized into the Mediterranean Air Command (MAC) under Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Tedder. The major sub-command of MAC was the Northwest African Air Forces (NAAF) under the command of Lieutenant General Carl Spaatz with headquarters in Tunisia. NAAF consisted primarily of groups from the United States 12th Air Force, 9th Air Force, and the British Royal Air Force (RAF) that provided the primary air support for the operation. Other groups from the 9th Air Force under Lieutenant General Lewis H. Brereton operating from Tunisia and Egypt, and Air H. Malta under Air Vice-Marshal Sir Keith Park operating from the island of Malta, also provided important air support. Army Air Force 9th Air Force’s medium bombers and P-40 fighters that were detached to NAAF’s Northwest African Tactical Air Force under the command of Air Marshal Sir Arthur Coningham moved to southern airfields on Sicily as soon they were secured. At the time, the 9th Air Force was a sub-command of RAF Middle East Command under Air Chief Marshal Sir Sholto Douglas. Middle East Command, like NAAF and Air H. Malta were sub-commands of MAC under Tedder who reported to Eisenhower for NAAF operations[19] and to the British Chiefs of Staff for Air H. Malta and Middle East Command operations. The island was defended by the two corps of the Italian 6th Army under General Alfredo Guzzoni, although specially designated Fortress Areas around the main ports (Piazze Militari Marittime), were commanded by admirals subordinate to Naval Headquarters and independent of the 6th Army. [26] In early July, the total Axis force in Sicily was about 200,000 Italian troops, 32,000 German troops and 30,000 Luftwaffe ground staff. The main German formations were the Panzer Division Hermann Göring and the 15th Panzergrenadier Division. The Panzer division had 99 tanks in two battalions but was short of infantry (with only three battalions), while the 15th Panzergrenadier Division had three grenadier regiments and a tank battalion with 60 tanks. [27] About half of the Italian troops were formed into four front-line infantry divisions and headquarters troops; the remainder were support troops or inferior coastal divisions and coastal brigades. Guzzoni’s defence plan was for the coastal formations to form a screen to receive the invasion and allow time for the field divisions further back to intervene. By late July, the German units had been reinforced, principally by elements of the 1st Parachute Division, 29th Panzergrenadier Division and the XIV Panzer Corps headquarters (General der Panzertruppe Hans-Valentin Hube), bringing the number of German troops to around 70,000. [29] Until the arrival of the corps headquarters, the two German divisions were nominally under Italian tactical control. The panzer division, with a reinforced infantry regiment from the panzergrenadier division to compensate for its lack of infantry, was under Italian XVI Corps and the rest of the panzergrenadier division under the Italian XII Corps. [30] The German commanders in Sicily were contemptuous of their allies and German units took their orders from the German liaison officer attached to the 6th Army HQ, Generalleutnant Fridolin von Senger und Etterlin who was subordinate to Generalfeldmarschall Albert Kesselring, the German C-in-C Army Command South (OB Süd). Von Senger had arrived in Sicily in late June as part of a German plan to gain greater operational control of its units. [31] Guzzoni agreed from 16 July to delegate to Hube control of all sectors where there were German units involved, and from 2 August, he commanded the Sicilian front. Two American and two British attacks by airborne troops were carried out just after midnight on the night of 9-10 July, as part of the invasion. The American paratroopers consisted largely of Colonel James M. Gavin’s 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment (expanded into the 505th Parachute Regimental Combat Team with the addition of the 3rd Battalion of the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment, along with the 456th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion, Company’B’ of the 307th Airborne Engineer Battalion and other supporting units) of the U. 82nd Airborne Division, making their first combat drop. The British landings were preceded by pathfinders of the 21st Independent Parachute Company, who were to mark landing zones for the troops who were intending to seize the Ponte Grande, the bridge over the River Anape just south of Syracuse, and hold it until the British 5th Infantry Division arrived from the beaches at Cassibile, some eleven kilometres (7 mi) to the south. [55] Glider infantry from the British 1st Airborne Division’s 1st Airlanding Brigade, commanded by Brigadier Philip Hicks, were to seize landing zones inland. Strong winds of up to 70 km/h (45 mph)[57] blew the troop-carrying aircraft off course and the American force was scattered widely over south-east Sicily between Gela and Syracuse. By 14 July, about two-thirds of the 505th had managed to concentrate, and half the U. Paratroopers failed to reach their rallying points. [58] The British air-landing troops fared little better, with only 12 of the 147 gliders landing on target and 69 crashing into the sea, with over 200 men drowning. [59] Among those who landed in the sea were Major General George F. The scattered airborne troops attacked patrols and created confusion wherever possible. A platoon of the 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment, under Lieutenant Louis Withers, part of the British 1st Airlanding Brigade, landed on target, captured Ponte Grande and repulsed counterattacks. Additional paratroops rallied to the sound of shooting and by 08:30 89 men were holding the bridge. [60] By 11:30, a battalion of the Italian 75th Infantry Regiment (Colonel Francesco Ronco) from the 54th Infantry Division “Napoli” arrived with some artillery. [61] The British force held out until about 15:30 hours, when, low on ammunition and by now reduced to 18 men, they were forced to surrender, 45 minutes before the leading elements of the British 5th Division arrived from the south. [61][62] Despite these mishaps, the widespread landing of airborne troops, both American and British, had a positive effect as small isolated units, acting on their initiative, attacked vital points and created confusion.