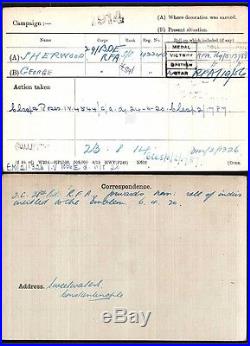

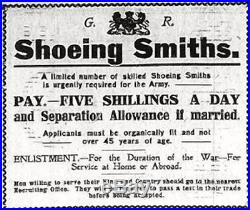

Comes with copies of documentation. Comes with original ribbon bar complete with rosette denoting award of the clasp. All ribbons are original, not modern copies. Documentation shows that George Sherwood was in 29th Brigade of the Royal field Artillery and arrived in France on August 23rd 1914. His address after the war is listed, interestingly, as “Sweetwaters, Constantinople”. The Medal information Card and Medal Roll show he was qualified for and awarded the 1914 medal clasp, which means he came under fire and did not remain at the rear. The trade of shoeing smith was a qualification within the British Army. Until the phasing out of horse transport after World War One in addition to cavalry &;amp;amp; artillery regiments, engineers, ordnance and service Corps all had farriers &;amp;amp; shoeing smiths trades within their ranks. Shoeing Smiths were blacksmiths and also had an understanding of the problems associated with horses’ feet and legs. Each medal is engraved to Sherwood as follows: 1914 Mon Star: 42240 S. Victory medal: 42240 SJT. Please look at the pictures for precise condition and please fell free to ask any questions. The 29th Brigade Royal Field Artillery War Diary 1914 Aug. 1919 Feb can be found at the National Archives in Kew (file WO 95/1466). It was part of the British Expeditionary Force’s 4th Division and its infantry arrived in France in time to be involved in the Battle of le Cateau. Its artillery and other supporting troops did not join it until a few days later. The Brigade consisted of three 18-pounder batteries (125, 126 and 127) but acquired a fourth battery, 128, armed with 4.5-inch howitzers, in May 1916. The 1914 Star, often referred to as the Mons Star. This medal was awarded to all officers, warrant officers, non-commissioned officers and all men of the British and Indian Forces, including civilian medical practitioners, nursing sisters, nurses and others employed with military hospitals; as well as men of the Royal Navy, Royal Marines, Royal Naval Reserve and Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, who served with the establishment of their unit in France and Belgium between August 5th 1914, and midnight of November 22/23rd, 1914. The decoration consists of a lacquered bronze star, the uppermost ray of the star taking the form of the imperial crown. Resting on the face of the star is a pair of crossed swords, and, on them, is a circular oak wreath. A scroll winds around the swords : it is inscribed with the date Aug. The ribbon is red merging into white and then into blue. 365,622 1914 Stars were issued as such it is by far the rarest of the First World War campaign medals. The soldier’s regiment and number are inscribed on the flat rear face of the Star. Clasp to the 1914 Star A bar clasp inscribed 5 Aug. 1914 was given to all those who qualified for the 1914 Star and who served under fire. Since the same ribbon is used with the 1914-15 Star, holders of the 1914 Star were permitted to wear a small silver rosette on their ribbon when the decoration itself is not worn. On the medal index cards this is usually noted as the “Clasp and Roses” or “C&;amp;amp;R”. It was necessary to apply for the issue of the clasp. The requirement was that a member of the fighting forces had to leave his native shore in any part of the British Empire while on service. It did not matter whether he/she entered a theatre of war or not. All men who served in the main theatres of war qualified for this medal, as did those who left their native shore for service in, for example, India. The medal is silver and circular. A truncated bust of King George V is on the obverse, while there is a depiction of Saint George on the reverse. There is a straight clasp carrying a watered silk ribbon. This has a central band of golden yellow with three stripes of white, black and blue on both sides. The blue stripes come at the edges. 6,610,000 British War Medals were issued. The soldier’s regiment and number are inscribed around the rim. The Victory Medal, 1914-19 This medal was awarded to all those who entered a theatre of war. It follows that every recipient of the Victory Medal also qualified for the British War Medal, but not the other way round. For example if a soldier served in a garrison in India he would get the BWM but not the Victory Medal. In all, 300,000 fewer Victory Medals were required than British War Medals. All three armed services were eligible. It is not generally known that Victory Medals continued to be awarded after the Armistice, for the British forces who saw action in North Russia (up to October 12th, 1919) and Trans-Caspia (up to April 17th, 1919) also qualified. The medal was struck in bronze. On the obverse is a full-length figure of Victory. On the reverse is the inscription “The Great War for Civilisation”. There is no clasp, but a ting attachment through which the ribbon is passed. The official description of the colour of the ribbon is “two rainbows with red in the centre”. 5,725,000 Victory Medals were issued. Horses in World War One The role and romance of horses in the First World War was depicted brilliantly in the 2011 film War Horse. Some 8 million horses and mules died in World War One. The use of horses in World War I marked a transitional period in the evolution of armed conflict. Cavalry units were initially considered essential offensive elements of a military force, but over the course of the war, the vulnerability of horses to modern machine gun and artillery fire reduced their utility on the battlefield. This paralleled the development of tanks, which would ultimately replace cavalry in shock tactics. While the perceived value of the horse in war changed dramatically, horses still played a significant role throughout the war. All of the major combatants in World War I (19141918) began the conflict with cavalry forces. Germany stopped using them on the Western Front soon after the war began, but continued limited use on the Eastern Front well into the war. The Ottoman Empire used cavalry extensively during the war. On the Allied side, the United Kingdom used mounted infantry and cavalry charges throughout the war, but the United States used cavalry for only a short time. Although not particularly successful on the Western Front, Allied cavalry did have some success in the Middle Eastern theatre, against a weaker and less technologically advanced enemy. Russia used cavalry forces on the Eastern Front, but with limited success. The military mainly used horses for logistical support; they were better than mechanized vehicles at traveling through deep mud and over rough terrain. Horses were used for reconnaissance and for carrying messengers, as well as pulling artillery, ambulances, and supply wagons. The presence of horses often increased morale among the soldiers at the front, but the animals contributed to disease and poor sanitation in camps, caused by their manure and carcasses. The value of horses, and the increasing difficulty of replacing them, was such that by 1917 some troops were told that the loss of a horse was of greater tactical concern than the loss of a human soldier. Ultimately, the blockade of Germany prevented the Central Powers from importing horses to replace those lost, which contributed to Germany’s defeat. By the end of the war, even the well-supplied U. Army was short of horses. Conditions were severe for horses at the front; they were killed by artillery fire, suffered from skin disorders, and were injured by poison gas. Hundreds of thousands of horses died, and many more were treated at veterinary hospitals and sent back to the front. Procuring fodder was a major issue, and Germany lost many horses to starvation. Several memorials have been erected to commemorate the horses that died. Artists, including Alfred Munnings, extensively documented the work of horses in the war, and horses were featured in war poetry. Novels, plays and documentaries have also featured the horses of World War I. In 1918, over half of Britains horses were in France, while the rest were spread out across Europe. The majority of the horses were not used on the battlefield. In 1918, just over 75,000 were allocated to the cavalry, while nearly 450,000 horses and mules were used to lug supplies around. Another 90,000 were charged with carrying guns and heavy artillery, and over 100,000 were horses who were ridden around the front lines, carrying food and ammunition to soldiers and bearing the wounded across the trenches to hospitals. The item “World War One Trio Medals Mons Star Clasp Shoeing Smith WAR HORSE Documented” is in sale since Saturday, May 20, 2017. This item is in the category “Collectibles\Militaria\WW I (1914-18)\Original Period Items\Great Britain\Medals, Pins & Ribbons”. The seller is “doubledeuce12″ and is located in McLean, Virginia. This item can be shipped worldwide.

- Country/Region of Manufacture: United Kingdom